Just like a heart attack can make your arm hurt, sore or tight muscles can send pain, tingling, or numbness somewhere else entirely. This is called referred pain, and after trauma it's the most common source of persistent symptoms that conventional care often misses.

A trigger point is a tight, tender spot in a muscle that refers pain to a distant area. It forms when muscle fibers stay contracted, creating a taut band with reduced blood flow. The muscle is stuck, and that stuck area sends signals far beyond its location.

After an accident or injury, your body protects itself by tightening muscles. If that protective tension stays too long, trigger points form. These tight bands keep sending pain signals even after the original injury heals, creating a pattern that outlasts the cause.

MRI scans don't show trigger points. EMG studies may detect muscle activity but don't localize the source. X-rays show bones, not muscles. The diagnosis requires manual examination, palpation, and recognition of referral patterns.

Trigger points create predictable pain patterns that don't follow nerve territories. Recognizing these patterns is key to finding the source.

Upper trapezius creates pain from the shoulder traveling up the neck into the head, often mistaken for tension headaches. Levator scapulae creates pain at the angle of the neck and shoulder, limiting rotation.

Scalene muscles in the front of the neck can refer pain and tingling down the arm into the thumb, mimicking carpal tunnel syndrome. Latissimus dorsi sends pain around the side and back, sometimes radiating down the inner arm.

These patterns often look like nerve compression, but the sensory changes are patchy and don't follow clean dermatomes. When you press the trigger point, you recreate the exact distant pain.

Gluteal muscles create deep ache in the buttock or down the lateral leg, frequently mistaken for sciatica. Unlike true sciatica, the pain doesn't typically travel below the knee and lacks the dermatomal distribution of nerve root compression.

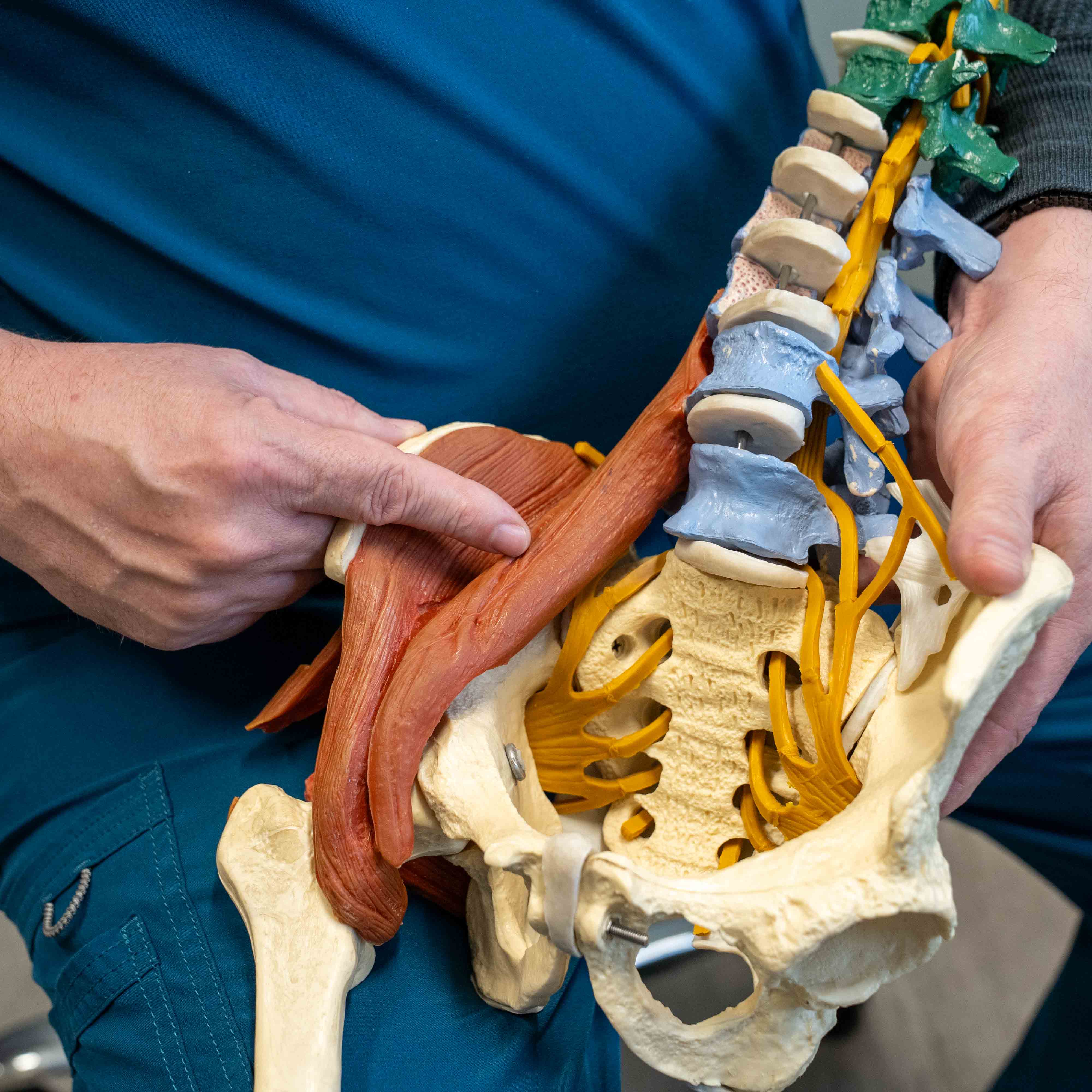

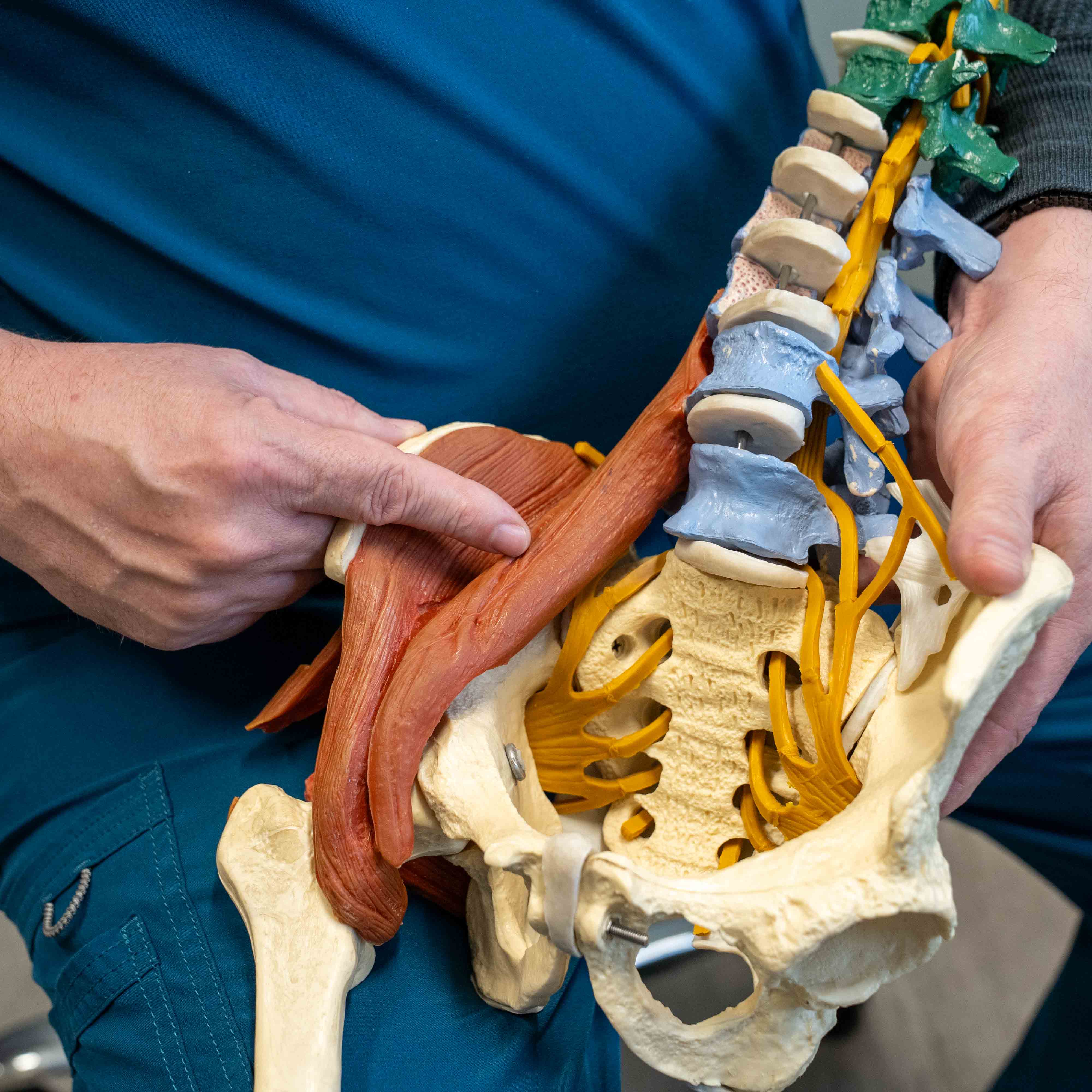

Quadratus lumborum creates deep flank and hip pain that can refer into the groin or lower abdomen. Piriformis can compress the sciatic nerve while also creating its own myofascial referral pattern.

The key distinction: when you press the muscle trigger point, the distant pain is reproduced. This is both diagnostic and guides treatment.

I start by listening to where you feel pain, numbness, or tingling. The pattern gives clues. Does it follow a nerve? Does it match a known myofascial referral pattern? Is it patchy and multi-dermatomal?

Most patients have already seen multiple providers and had imaging. Often the imaging shows findings that don't explain the symptoms. This is when myofascial sources become more likely.

The defining test: pressing the muscle trigger point recreates your distant pain. If I press your upper trapezius and your head pain appears, that's the source. If I press your gluteal muscles and your leg pain reproduces, we've found it.

This is why palpation is essential. No scan can replace the diagnostic information gained from systematic manual examination of muscles.

For complex cases where symptoms mimic nerve compression, I use sensory mapping to plot exactly where sensation is altered. A patchy, non-dermatomal pattern supports myofascial origin. A clean dermatomal stripe suggests nerve root involvement.

This visual map helps distinguish muscle-based referral from true neurologic pathology, preventing unnecessary testing or intervention.

Once we identify the trigger point, treatment becomes targeted. The goal is to release the taut band, restore blood flow, and allow the muscle to relax.

I use a fine needle to activate the trigger point, then introduce a small volume of sterile saline. The gentle hydrostatic pressure adds internal stimulation, helping the taut band release more completely. This avoids the sting of local anesthetic while combining needling with pressure-based release.

After releasing the trigger point, we focus on lengthening the muscle and strengthening opposing muscle groups. This prevents recurrence and restores balanced mechanics. Gentle massage and heat can help maintain the release.

Trigger points often form because of sustained postures or repetitive movements that overload certain muscles. Addressing ergonomics, breathing patterns, and movement habits prevents the cycle from restarting.

When the trigger point releases, the referred pain resolves, often immediately and dramatically. This confirms the diagnosis and provides relief that's been elusive with other approaches.

Patients with myofascial pain often undergo extensive testing, imaging, and even surgery for problems that don't exist. They're told their pain is "in their head" or that they need to "learn to live with it."

The reality is simpler: the source is in the muscle, and it's treatable. Once we find the trigger point and release it, function returns and pain resolves.

This isn't about managing chronic pain. It's about identifying the mechanical source and fixing it.

If your pain doesn't make sense, if imaging doesn't explain it, if nothing else has worked, the answer might be in your muscles. Let's find the trigger point and release it.

Schedule Consultation